I’m going to do something extremely unchic on the Wex Photo Video blog, and talk about a video game. I’m sorry. I promise to be brief.

The video game in question is Deus Ex: Human Revolution. Released a decade and a half ago, it’s a cyberpunk action-adventure set in a near-future society on the verge of collapse. The protagonist and player character is a man named Adam Jensen, a private security contractor who, after suffering a series of debilitating injuries, gets cybernetically “augmented” with robotic body parts.

Adam Jensen’s feelings about these body parts are conflicted to say the least. There’s a phrase that has become commonly associated with him, to the point of becoming a meme, even though he doesn’t say it all that much in the game itself:

The reason I bring this up — and the reason you laboured through those last couple of paragraphs, thank you for that — is because I’m thinking about Adam a lot lately. Every time a press release plops into my inbox informing me of yet another way that generative AI has been shoved into some aspect of the technologies I use, I hear the gravelly tones of Adam Jensen’s eminently capable voice actor Elias Toufexis. Always the same words.

“Generative AI images come to PDF for the first time!” says my email. “I never asked for this,” my brain replies.

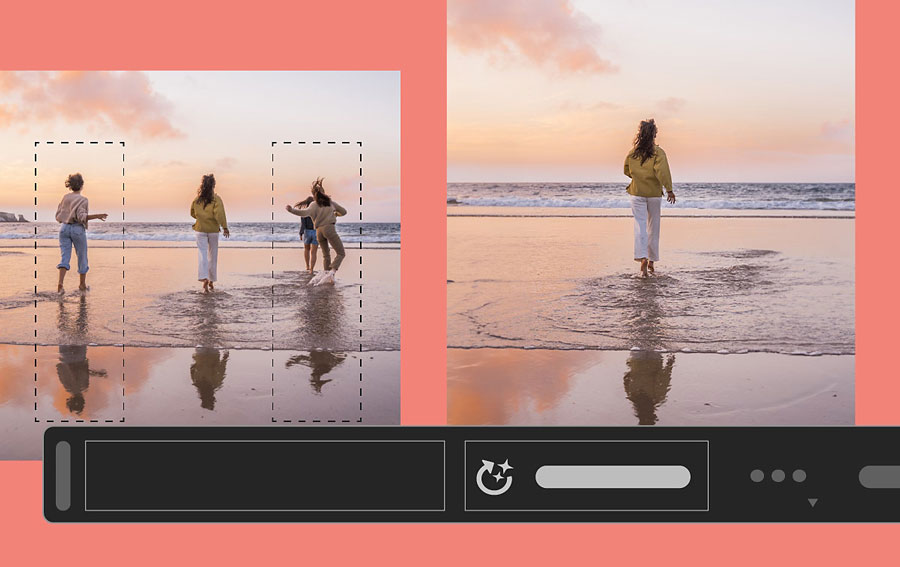

“Lightroom adds additional AI-powered innovations including Lens Blur to add aesthetic blur effects in a single click.” Okay, great, but the thing is: “I never asked for this.”

“The integration of ‘Generate Image’ [into Photoshop] shortens the distance between the blank page and stunning results.” I’m sure it does. However.

It plays on a loop. But I think my poor subconscious brain does have something of a point, because the thing is, I really never did ask for any of this. And I’m willing to bet you didn’t either.

© Adobe

The future of the past

If you’d polled some photographers or photography critics in, say, 2009 or 2010 about what they hoped or expected photography would look like fifteen years in the future, do you reckon a single one of them would have expressed a desire for computer programs to fully hallucinate parts of a photographic image?

Well you don’t have to reckon, because we can look back at the internet of the time and see that the answer is no. Here, for instance, are ten documentary photographers in the year 2010 talking about the possible futures for their craft (apologies for the broken HTML and dead links throughout; link rot is a real problem). You’ll note that several of them talk perceptively about the rising importance of video, and the increased primacy of the screen as the window to the world. You’ll also note that not a single one of them expresses an expectation or a desire for a computer program that can make up an image that never existed.

Or, take a look at this MIT piece from 2009 by Kate Greene on the future of “computational photography”, which makes for extremely interesting reading now. The researchers interviewed describe a future where “anyone can use a camera with a small, cheap lens to take the type of stunning pictures that today are achievable only by professional photographers using high-end equipment and software such as Adobe Photoshop.”

One of the most amusing moments from a modern perspective comes when the article discusses a hypothetical photo-editing tool that would be able to remove the kind of image blur caused by using a lens with a shallow depth of field — the same blur that Adobe is now gleefully promising that its generative AI tools will be able to put back in.

Again, at no point do the researchers predict that photographic tools will be able to invent parts of images out of thin air — though at this point I’m obliged to point out that, of course, generative AI images aren’t really generated at all; they are scraped, harvested and stitched together from the work of actual photographers and artists. In our interview with AOP president Tim Flach we went into detail on this, and Tim summed it up with characteristic succinctness:

“Most people don’t appreciate that the AI system has no capacity without first parasitically absorbing images to train itself. A generative AI – which is distinct from general artificial intelligence – is something that’s prompted at one end and spits something out at the other.”

You can’t really blame the researchers in the MIT article for not predicting this stuff, at least in my view. Their work was predicated on looking through the lens of tools and functions that photographers would conceivably want. And what kind of company would invent, develop and market something that nobody actually wants?

Adobe

The three quotes I included in the first section of this piece were all taken directly from Adobe press releases I received. Something I didn’t mention, though, is that all three of them were sent to me within the span of about one month, between late April and early June 2024. You would not be wrong to describe Adobe’s AI fixation with words like “relentless”.

© Adobe

It is impossible to talk about the relationship between photography and AI without talking about Adobe, which is something the company would no doubt be pleased about, even though I don’t mean it as a compliment. Adobe is being extremely bullish about incorporating generative AI into every aspect of its offering, and the cloud-based nature of its editing programs like Photoshop and Lightroom means you’re getting it, whether you want it or not.

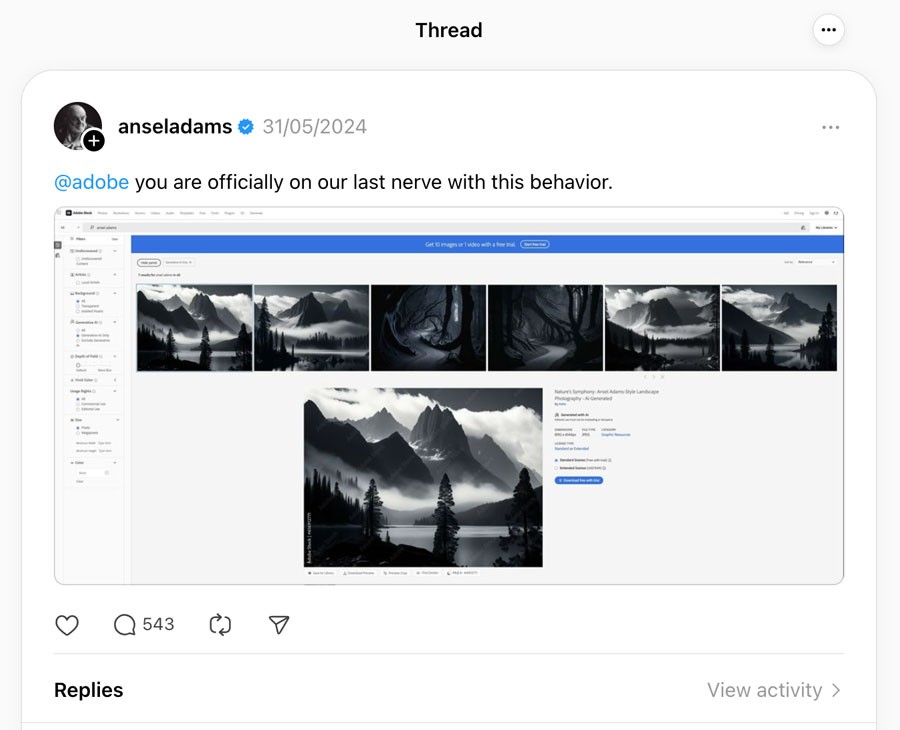

This rollout has not been without its complications. In May 2024, the Ansel Adams estate directly called out Adobe on Threads for selling AI-generated images that were labelled as “Ansel Adams style” on its Adobe Stock service — which allows for the uploading and selling of AI-generated images, though not ones explicitly flagged as being in the style of a copyright-holding photographer.

© Ansel Adams Estate

Adobe apologised and took the offending images down, thanking the estate for flagging the content and encouraging it to reach out to them directly if this happened again. The Adams estate’s public response to this is worth quoting in full:

“Thanks @adobe but we’ve been in touch directly multiple times beginning in Aug 2023. Assuming you want to be taken seriously re: your purported commitment to ethical, responsible AI, while demonstrating respect for the creative community, we invite you to become proactive about complaints like ours, & to stop putting the onus on individual artists/artists’ estates to continuously police our IP on your platform, on your terms. It’s past time to stop wasting resources that don’t belong to you.”

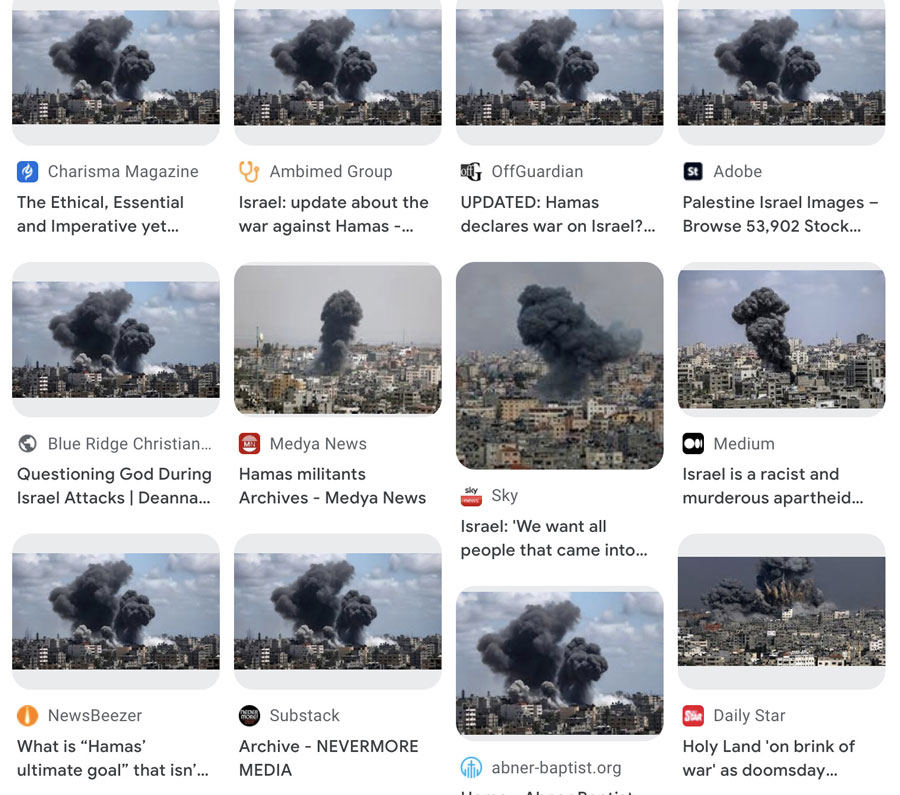

The issue also extends beyond copyright infringement. In November 2023, crikey.com reported that Adobe Stock was selling AI-generated images of the war in Gaza, which were then used across the internet by news outlets without any indication that they were fake. Adobe issued a rather lukewarm response, saying that the images had been “labeled as generative AI when they were both submitted and made available for license in line with these requirements.” So, it’s fine actually.

Shortly after this story broke, I paid an early cancellation fee to terminate my Creative Cloud subscription. That isn’t relevant; I’m just still bitter and wanted to mention it.

There’s a clear pattern here, of technology being pushed on users who haven’t asked for it, in a way that generates confusion and anger and is easily exploitable by bad actors. And a company that is not even for a second considering changing course in response to this. The extra-brilliant news is that Adobe is far from the only offender in this regard.

Meta

If you spent much time on Instagram over the past couple of months, you probably have noticed a text template spreading across people’s stories, in which users loudly proclaim that they do NOT give Instagram permission to train its AI models on their images and videos, following announced changes to its privacy policy. Instagram, a company that is perhaps unsurpassed in terms of sheer, naked, withering disdain for its users, will be going ahead with this scraping anyway. There are some confusing opt-out options that vary depending on where you’re located, though ultimately, there is only one surefire way to stop Instagram from training AI models using your images, and you already know what it is.

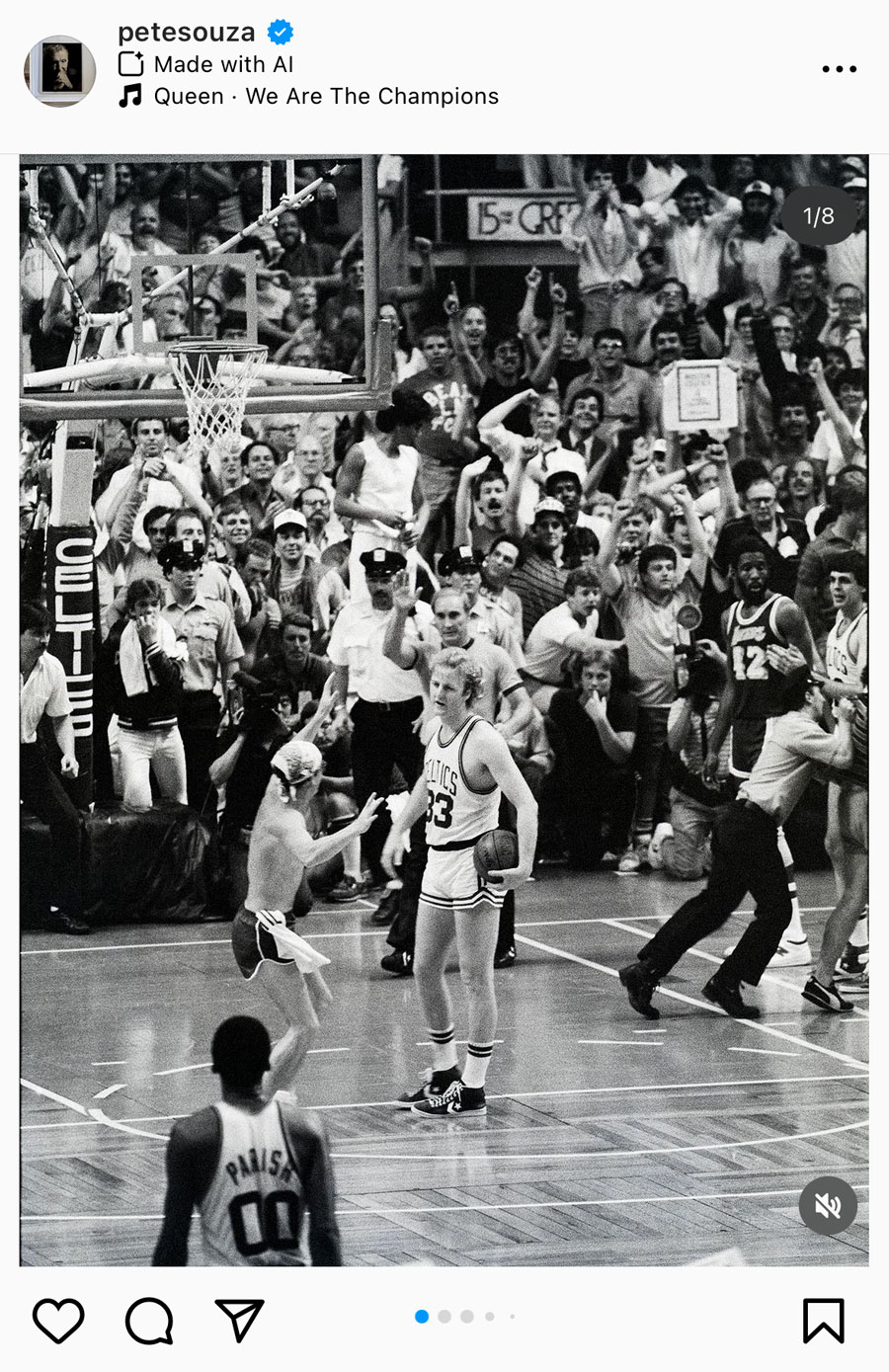

However, Meta and Instagram have also managed to get themselves caught up in an entirely different AI-based controversy. You may have noticed the little “Made with AI” tag that has started to appear on certain Instagram posts. You may also have noticed that often the people who made those posts will end up adding in the comments, with understandable irritation, that the posts were not in fact made with AI. Notable accounts such as that of former White House photographer Pete Souza have had their images incorrectly tagged with the unremovable label. What’s happening there?

Well, Meta isn’t exactly a company known for its transparency, so nothing has been exactly confirmed, but the best guess seems to be that its algorithm is picking up on images that have been processed by our old friend Adobe Photoshop and its generative fill tools. Souza told TechCrunch that he had cropped his image in Photoshop before saving it as a JPEG, and thereafter was forced to add the “Made with AI” tag with no option to uncheck it.

© Pete Souza

Meta claims that the labelling system is part of an effort to improve transparency and help people know when they’re seeing an AI image. This may well be true, though one might also point out that the AI industry is one that’s still largely built on hype, on the promise of what the product will soon be able to do, more than what it currently does.

Like those “Bitcoin accepted here” stickers you used to see in the windows of shops (none of which would actually accept Bitcoin), the “Made with AI” tag does the job of normalising AI images to the public, making them routine and expected, and thereby giving the algorithm’s programmers an incentive to get it flagging as many images as possible.

I don’t know if this was actually Meta’s thinking with this tag, though it does make sense. But it is undeniably depressing to watch this AI ouroboros at work — as an unasked-for AI algorithm merrily attaches itself to real photographs, because they have been edited using a program stuffed with unasked-for AI features. On the whole it’s not what you’d call “good”.

As much energy as a small country

Here’s a stat I think about a lot: just five prompts in ChatGPT can require as much as half a litre of water, according to research from the University of California. Here’s another from that same link: Microsoft’s water consumption jumped up by 34% from 2021 to 2022, climbing to almost 1.7 billion gallons, which the company’s own environmental reports attribute to its AI research (the company first partnered up with OpenAI in 2019). Google, with its “Best Take” and “Magic Eraser” features now obligatory in Pixel phones, has seen its water consumption increase by 20% over a similar period.

AI uses as much energy as a small country, and researchers who are tracking it expect this consumption to double by 2026, with tech companies showing absolutely no sign of backing off from it.

Such breathless waste is difficult to get your head around. All that water, all that power, for what? So that photographers can swap out a lacklustre sky for one that never existed? So that online hucksters can profit off the name of Ansel Adams, or sell fake images of war to overworked or sloppy picture editors? Was anyone — anyone at all — truly asking for this?

To be as fair as possible, there are two categories of people who were and are asking for this. The first and most obvious is the investor class — the shareholders, the tech executives, and basically anyone who stands to directly profit from widespread adoption of this technology.

And the second? Well, there’s no real polite way of saying this, so — it’s lazy people. Students who want to cheat on their homework. People who want to feel like an artist without having to go through the bothersome business of learning to make art. Photographers who want to win a competition without having to wait for the perfect light at the perfect time, and so are willing to make the computer insert that light instead. For these people and no others, we must reopen coal plants, guzzle water by the pool-load, and choke our already polluted atmosphere. There is, we are told, no alternative.

About a year ago, I wrote a piece for Wex thinking about how the photography world should respond to AI. I took quite a conciliatory attitude, trying to think about how photographers and the photography community, from competitions to publishing, could co-exist with these technologies. Well, twelve months have radicalised me, and I am happy to admit that I was wrong. There is no co-existing with this stuff while it rips off your images, compromises the already degraded trust in the public sphere, and worsens our rapidly escalating climate crisis. If you care about photography, or video, or the truth, I believe you have a responsibility to reject this technology wherever you can.

Because we never asked for this. Any of this.

About the Author

Jon Stapley is a London-based freelance writer and journalist who covers photography, art and technology. When not writing about cameras, Jon is a keen photographer who captures the world using his Olympus XA2. His creativity extends to works of fiction and other creative writing, all of which can be found on his website www.jonstapley.com