The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy defines an indexical as "an expression whose reference on an occasion is dependent upon the context: either who utters it, or when or where it is uttered, or what object is pointed out at the time of its utterance. The terms I, you, here, there, now, then, this, and that are indexicals."

In photography, indexicality refers to the direct relationship between the photographer, the photograph, and the subject. This concept emphasises that photographs are inherently linked to the physical reality they capture, serving as an imprint of the real world. Unlike paintings or drawings, which are interpretations or imaginations, photographs are created through a mechanical process that records light from the subject. This direct correlation implies that a photograph serves as visual evidence of existence, providing an authentic link between the photographer, the photograph, and the subject.

But is the Indexicality of photography still a viable concept today? We live in a visual culture meaning we must be able to read and interpret images to help us understand the world. Photography has a complex relationship with the truth; since its inception, there has been manipulation of the truth. Today, AI and digital photo manipulation further undermine the authenticity of artistic creation and journalistic practices. How can we trust the connection between photographs and their representation of reality in this context?

Historical context of indexicality in photography

In the 1800s, American philosopher Charles Peirce categorised the signs we use to communicate ideas with each other into three types; icon, index and symbol. An icon has a “close physical resemblance to what it signifies”, and a symbol “has no resemblance between the signifier and signified at all. It is our framework of knowledge which helps us understand the meaning of these signs.” An example where both are used in one is a no-smoking sign. The icon of the cigarette is recognisable as what it is; a cigarette. The symbol of a red ring with a line through it has no semblance to anything, but our societal framework suggests whatever that symbol is stamped on, is prohibited.

Peirce’s definition of “index” was a sign that shows evidence for the existence of what it refers to e.g. a footprint or a crack. In terms of photography, indexicality refers to the fact that a photograph is created by the direct action of light on a photosensitive surface. This process provides a level of accuracy and authenticity unique from other art forms like painting and drawing, which rely on an artist's interpretation and ability to portray a scene accurately.

In the early 1900s, this notion and similar ideas led to photography being valued as an objective representation of reality. Photographers documented the world as it was, with the mechanical processes of cameras minimising human intervention and reinforcing the belief in its objectivity. This seemingly eliminated human bias. Along with its early use in scientific documentation, cameras helped develop photojournalism, offering a way to truthfully share news and events as they happened, rather than through word of mouth.

The dawn of photojournalism

Henri Cartier-Bresson was a pioneer in the field of photojournalism. In 1957, he coined the phrase “the decisive moment”; a concept that implies a photographer must be present in a scene and it is his or her capture of a fleeting moment that reveals a deeper truth about the subject. His images were a direct reflection of reality.

In truth, he didn’t exactly intend to coin the phrase. In 1952, he published a photo book titled Images à la sauvette, which was translated in the English edition as The Decisive Moment. However, the French title actually translates to "images on the sly" or "hastily taken images." In fact, it is said that “Cartier-Bresson disliked the title The Decisive Moment given to his early book of photographs. A truer translation from French would have been “images on the run.”)

In an interview with the Washington Post in 1957 Cartier-Bresson said "Photography is not like painting…”; “there is a creative fraction of a second when you are taking a picture. Your eye must see a composition or an expression that life itself offers you, and you must know with intuition when to click the camera. That is the moment the photographer is creative" and "once you miss it, it is gone forever."

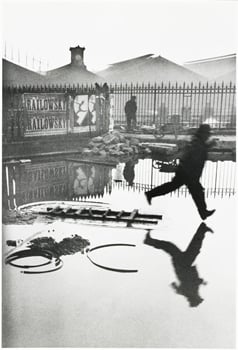

A fantastic example is his photograph "Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare" (1932) which captures a man leaping over a puddle. It is a perfect instance of the decisive indexical moment, freezing a moment in time with no opportunity for staging or alteration.

© Henri Cartier-Bresson - Behind the Gare St. Lazare

Modern camera tech

We discussed that the inherent indexicality of a photograph is achieved by the direct action of light on a photosensitive surface. But can the same be said for a digital photograph? What impact have digital advancements had on indexicality?

Consider this: a photographer is present with a top-of-the-line mirrorless camera. They witness a moment in time, press the shutter, light enters the lens, and an image is digitally recorded on the sensor. I see no problems. But can the internal processes of modern cameras blur the lines of reality? Automatic focusing, aperture, and ISO changes are designed to aid in the effective capture of the scene, but do they affect the authenticity of the image?

After all, even historic cameras allowed users to adjust aperture or use more sensitive ISO film to capture photos better. Therefore, as long as these features are used to support, rather than alter, I would argue the indexical link between the photograph and reality remains largely intact.

Tom Gunning says the “difference between the digital and the film-based camera has to do with the way the information is captured…” He suggests that the fact that rows of numbers (digitally stored photographic data) do not look like a photograph or what the photograph represents does not weaken any indexical claim. The indexicality of a traditional photograph lies in the effect of light on chemicals, not the resulting image. Similarly, both digital camera data and traditional photographic images are determined by external objects and in both cases, complex procedures are needed to produce the final image.

Despite modern cameras' automatic processes and digital data, these features support rather than alter the captured scene, meaning authenticity remains largely intact. As Tom Gunning suggests, the difference between digital and film photography lies in how information is captured, not in their indexical relationship to reality.

Other photography technology

So what about other forms of technology within photography? An obvious form would be the manipulation of lighting. The use of artificial lighting or even reflectors, scrims and flags directly alters what a camera sees and therefore reality. Surely, the philosophers of the 17th century would take issue with this and argue that a photo with such human intervention was not a true representation? But just because they may say so, should they stop us from using the advances in technology to take “better” pictures? Most certainly not. When it comes to photojournalism, reportage, sports, events etc. the correct use of these technologies helps to maintain a photo’s indexicality and authenticity. I’d argue that an ethical use of technology does not necessarily impact the indexicality of a photo.

Of course, this is a somewhat narrow view when there are many other forms of photography where indexicality doesn’t apply. Fashion, food, fine art, and abstract art are all forms of photography in which the photos are intentionally altered. Fashion and food photography are intentionally altered to give the best possible representation of the subject (sometimes better than real life). Fine and abstract art by nature, deviates from “reality”. Perhaps in modern photography, it comes down to the intention of the user and the context of the image as to whether we still have a true indexical representation of reality.

Ethical implications

I mentioned I see no problems with the idea of a person simply using a camera for its purpose as its impact on indexicality should be negligible. But realistically, it must come down to the intention of the photograph and/or the person taking it. For example, take the photographer during the Covid pandemic who used a telephoto lens to make it seem like beaches were full of lockdown breachers; that photo was intentionally taken to cause alarm. In this instance, technological advancements and an understanding of how a telephoto lens can compress an angle of view and distort a scheme removed the authentic link between the photograph and a true representation of reality.

Turn our attention to photo manipulation, at what point does the act of manipulating a scene void its authenticity? Revisiting Gunning’s essay, he discusses faking photographs, mentioning that “the power of the digital (or even the traditional photographic) to “transform” an image depends on maintaining something of the original image’s visual accuracy and recognizability.” This could suggest that as long as an image still strongly resembles the original photo, its authenticity can be maintained. Removing a blemish, wrinkles or sensor dust, that’s okay, right?

Classic photographer Bill Brandt often took issue with the idea of “aesthetic and technical rules some photographers imposed on themselves” such as Cartier-Bresson’s exclusive use of available light, unposed scenes and no-cropping. He said that,

“Photography is not a sport. It has no rules. Everything must be dared and tried.”

Brandt often created montages by combining sections of various negatives. He would even revisit images years later to add more sections such as one example from The English at Home (1936). The original photograph of a seagull was edited onto another photo of the Thames River in the darkroom. “A few years later Brandt added a morning sun to the scene.” This highlights that image alternation isn’t exclusively a digital phenomenon.

But in today’s society, it’s more and more difficult to trust the images we see. The availability and ease of photo manipulation have distorted our trust in the images we see. What likely began with the awareness of extensive editing in the fashion industry — altering images to create an idealised and unrealistic beauty standard — has now spread to all areas of the industry. Perhaps most worryingly, photojournalism and political reportage are plagued with doctored images that have the power to sway the views of the many.

And of course, that enormous digital AI elephant in the room has become so sophisticated so quickly, that it has become increasingly difficult to assess what is an authentic image. You can also see here where the BBC has highlighted how “people can easily make fake election-related images with artificial intelligence tools, despite rules designed to prevent such content.” It is a highly controversial topic and I’d rather not dwell on AI intervention too much as we have several pieces on the state of play that can be found here, here and here — generative fill this, destroy the lives of artists and creativity on the whole that.

So, what does this all mean?

If you're aiming to capture reality as a photographer, relying too heavily on advanced technology to manipulate photos undermines the essence of photography's truthfulness. Even if the edited result appears untouched, it distorts reality. This crumbles the trust we place in photos we read and interpret to help us understand the world.

In today's photography, maintaining the indexicality of capturing reality doesn’t have to stray far from its origin. The technology built into cameras and accessories can help ethical photographers accurately and authentically document the world around us. However, as technology advances, the future of photography is in flux. Tools like AI elevate image quality and creativity, but they also allow for manipulation and AI-generated content, blurring reality, undermining indexicality and taking away from the creative industry. Maintaining authenticity demands a conscious effort from photographers to consider authenticity and the connection between their photographs and the image of the world they represent.

About the Author

Leo White has been part of the Wex Photo Video team since 2018, taking on roles from the contact centre to the product setup team. Holding both a BA and an MA in photography, Leo brings a wealth of expertise he’s always ready to share.

Sign up for our newsletter today!

- Subscribe for exclusive discounts and special offers

- Receive our monthly content roundups

- Get the latest news and know-how from our experts